We may earn revenue from the products available on this page and participate in affiliate programs. Learn More ›

Very few workshop tasks can be as satisfying as putting a wood plane through its paces. There you are, just you and, say, a molding plane, standing over a board fixed in place on the workbench. Your first stroke is gentle, even tentative, as you establish the line you will follow. After a few more passes, your stroke now strong and sure, the profile begins to appear. Pretty soon, there’s a molding there, a bead or an ogee or a quirk ovolo.

Whatever the planing task before you or the type of plane to be used, there are some constants. One is balance: Get positioned so that you can use your weight and the strength in your shoulders and upper body. This isn’t work for the lower arms alone. The work- piece should be clamped at a comfortable height in front of you.

Most planes work best two-handed, with the left hand guiding the plane at the front, the right driving from the rear. You may also find that positioning the front hand so that the fingertips or the heel of the hand just brush the stock may help guide your stroke.

Trueing an Edge. Use the longest plane you have, preferably a jointer or jack plane. The longer the plane, the less it will exaggerate any existing troughs and crests cut into the edge. Clamp the stock to be planed in a vise, then set the plane at the end of the piece. Work with the grain. Before pushing the tool along the length of the board, apply some pressure at the front of the plane to be sure the sole sits flush to the piece (rather than on an incline, with the toe lifted above the piece). Likewise, be sure the heel sits flush to the board as the plane reaches the end of the planing stroke, shifting some of your weight to the back of the tool. This prevents “dipping,” in which more wood is planed from the ends than from the center of the stock.

Lift the plane at the end of the stroke, and carry it back to the starting point. Don’t drag it backwards. Plane irons get dull quickly enough without unnecessary wear and tear. Check the flatness of your work with a straightedge as you go along. A steel framing square will do.

Smoothing Flat Stock. This is a two-step process if you are using unplaned stock or if the workpiece consists of glued-up pieces. For hardwoods, begin by planing diagonally to the grain, perhaps at a forty-five- degree angle, more with some hardwoods. Use a long-soled bench plane like a jack or, for a large workpiece such as a tabletop, a jointer plane.

The iron must be set to plane very fine shavings (thicker shavings will tend to tear the grain). Work from side to side, planing one way and then the other, until the surface is level.

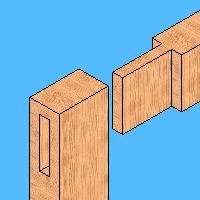

Cutting a Rabbet. This may seem to defy reason, but the rabbet is most easily started at the forward end of the workpiece. Use short strokes at first, gradually moving farther back on the piece. If the plane you are using has a depth stop, work until it contacts the workpiece and stops the planing. If the plane has no depth stop, work to a line you have left with a marking gauge.