We may earn revenue from the products available on this page and participate in affiliate programs. Learn More ›

Home Advice You Can Trust

Tips, tricks & ideas for a better home and yard, delivered to your inbox daily.

By signing up you agree to our Terms of Service and Privacy Policy.

Hearthstone Historic House Museum in Wisconsin

Wikimedia Commons via Carol Highsmith Archive

This Appleton, Wisconsin, home was the first in the United States to be lit via hydroelectric power sourced from the Appleton Edison Light Company. Built in 1882 by businessman Henry James Rogers for his wife, this Queen Anne Victorian may be the only surviving example of wiring and fixtures in their original location from the early days of the electrical age. If you visit the museum between November and January, you’ll see the house all decked out for the holidays.

Cragside in England

Wikimedia Commons via piotr.wassermann

Located in the town of Rothbury in Northumberland, Craigside was the home of industrial magnate and inventor William Armstrong. The stately manor attracted famous visitors, including the Shah of Persia, the King of Siam, and, in 1884, the Prince and Princess of Wales, but its fame today derives from its (at the time) state-of-the-art technology. By harnessing the power of water, Armstrong equipped his home with a hydraulic dumbwaiter, washing machine, and rotisserie. In 1878, he installed what is considered to be the first hydroelectric station, which powered the farm buildings as well as the house, making Cragside the first house in the world to be lit by hydroelectric power.

Charles Gates Mansion in Minnesota

Minnesota Historical Society

Today, most Americans expect the comfort of air conditioning wherever they go, but that was not always the case. Summer used to mean sweating, indoors and out. But that started to change in 1914, when the Charles Gates mansion became the first home to be outfitted with a cooling system. Unfortunately, Gates never had the chance to enjoy the cool breeze from his 7-foot-tall air conditioner; he died on a trip in 1913, before the house was completed. The mansion was demolished in 1933.

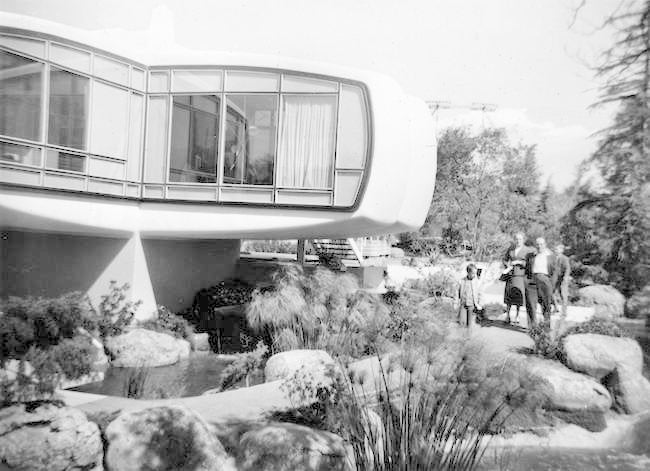

Frances Gabe's Self-Cleaning House in Oregon

US Patent #4428085

Some homeowners find cleaning to be a satisfying, soothing chore, while others, like Frances Gabe, hate it so much that they go to great lengths to avoid it. Tired of the daily cleaning grind, Gabe turned her home into a self-cleaning marvel in the 1970s. The revamped space was outfitted with sprinklers that sprayed both water and soap to wash surfaces. Drainage holes helped with drying, and delicate items were relegated to waterproof containers to prevent damage. The house eventually became too costly to keep up, and the self-cleaning home—although patented in 1984—never became a mass-produced reality.

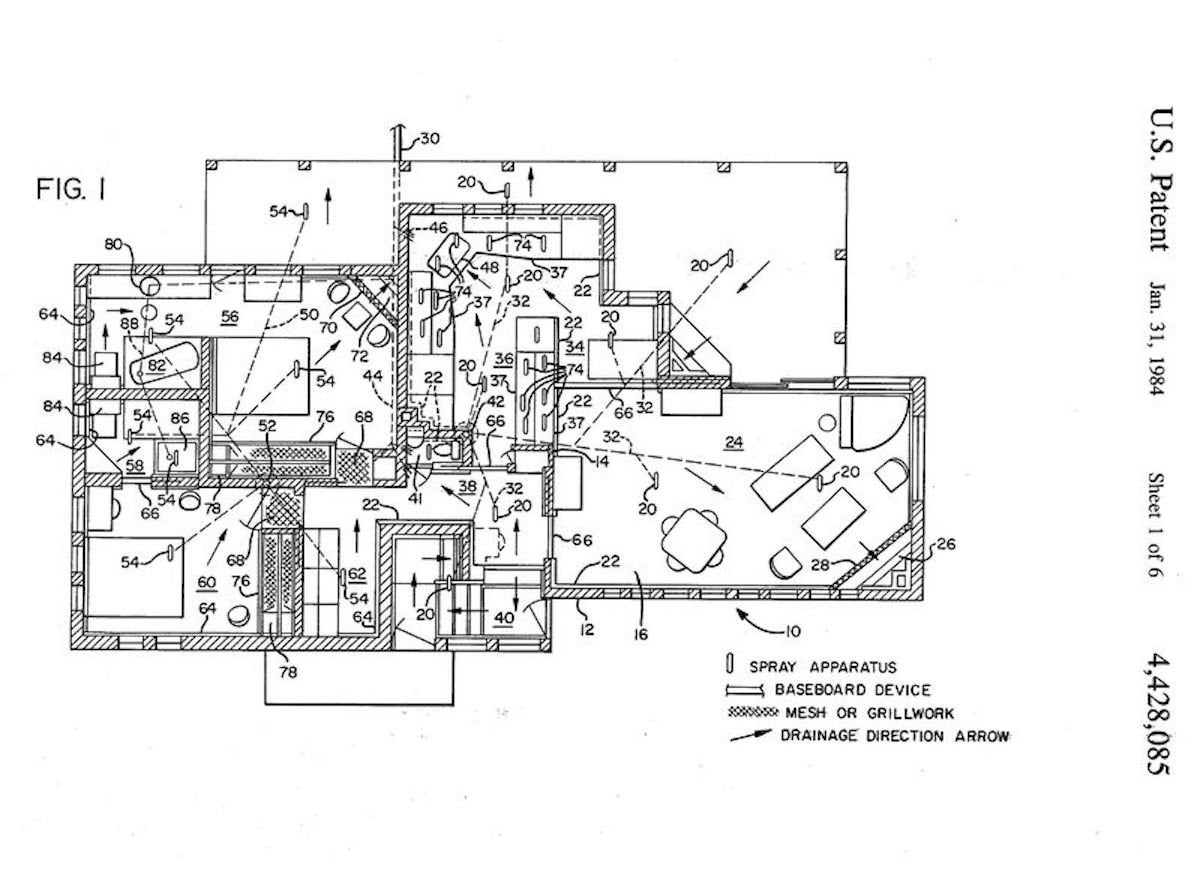

Dover Sun House in Massachusetts

The Dover Sun House, completed in 1948, was the first home to be heated by the sun. MIT researcher Maria Telkes developed the technology, which used a system of panels and stored sodium sulfate to soak up and conserve heat from the sun’s rays. This pioneering effort was not entirely successful; by 1954, the solar heating system had been replaced with a conventional furnace. But this project paved the way for later advances, and Telkes continued to be an innovator in solar power technology

Charles Williams Jr. House in Massachusetts

flickr.com via binarydreams

The first permanent residential telephone line was installed in the Charles Williams Jr. House in 1877. Williams was a manufacturer of telegraph instruments, and Alexander Graham Bell and Thomas Watson conducted experiments at his shop. A phone line was installed between Williams’s home and his shop, which were given the first two phone numbers of the Bell Telephone Company—1 and 2.

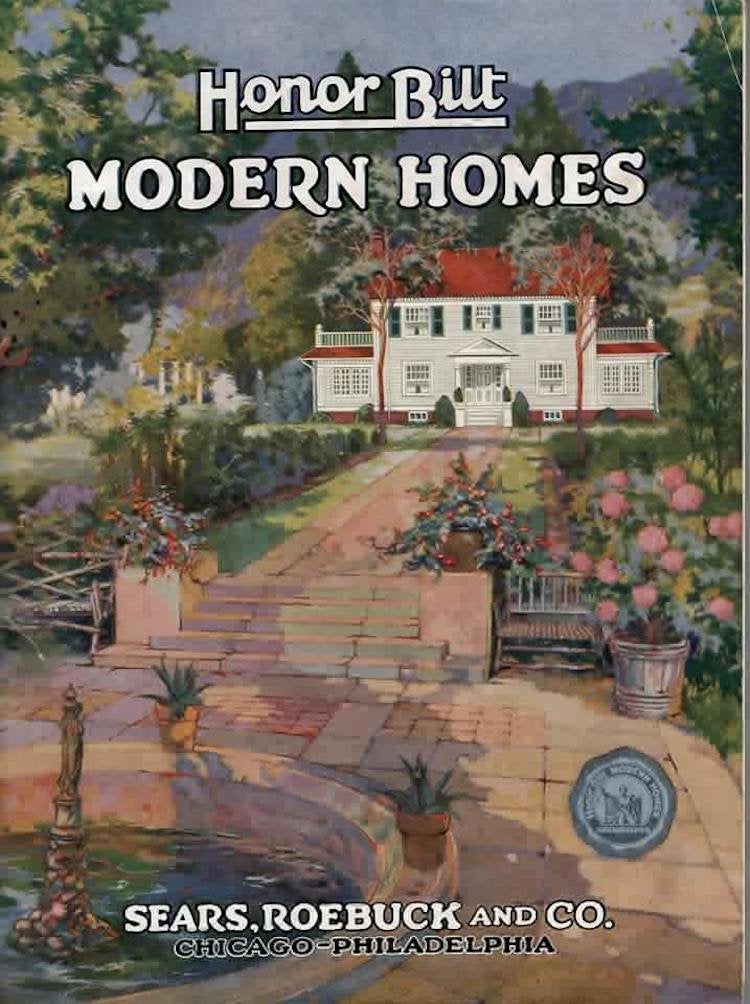

Sears Catalog Homes

Prefab housing is enjoying a comeback now that tiny, ready-to-go homes are all the rage. But the history of kit houses dates back more than a century. Sears, along with a number of other companies, offered hundreds of home designs to eager buyers who would order kits that included blueprints, instructions, precut lumber, paint, and hardware—practically everything needed to construct the home. (Sears didn’t provide masonry, and plumbing, heating, wiring, and other elements were sold as extras.) Thousands of these homes are still standing today, but they can be tricky to identify because sales records were destroyed sometime in the 1940s and renovations have made many of them look quite different from their original catalog illustrations.

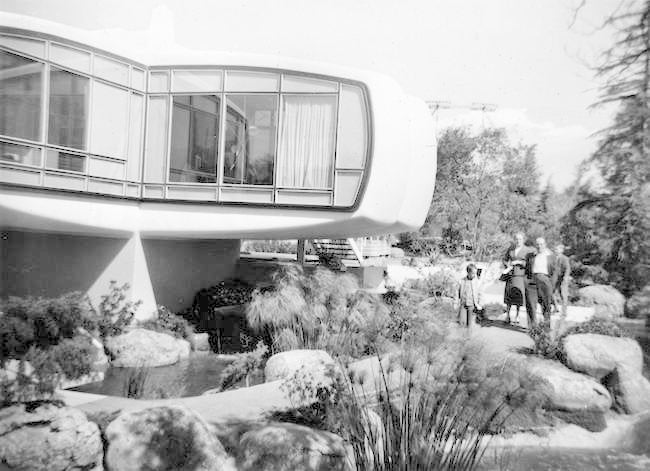

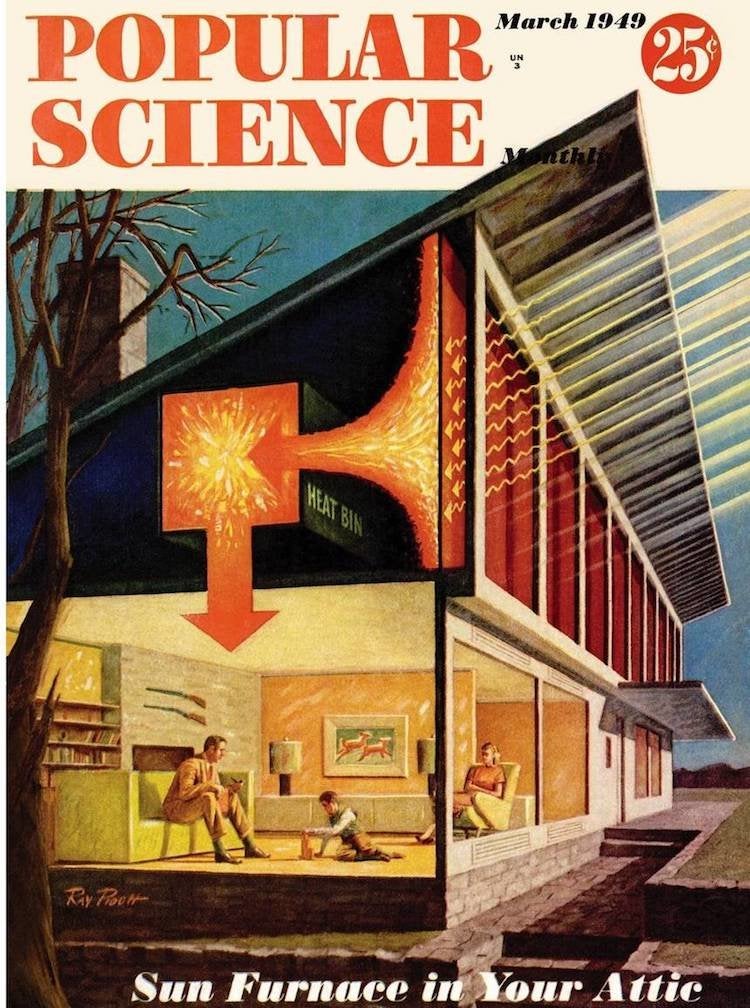

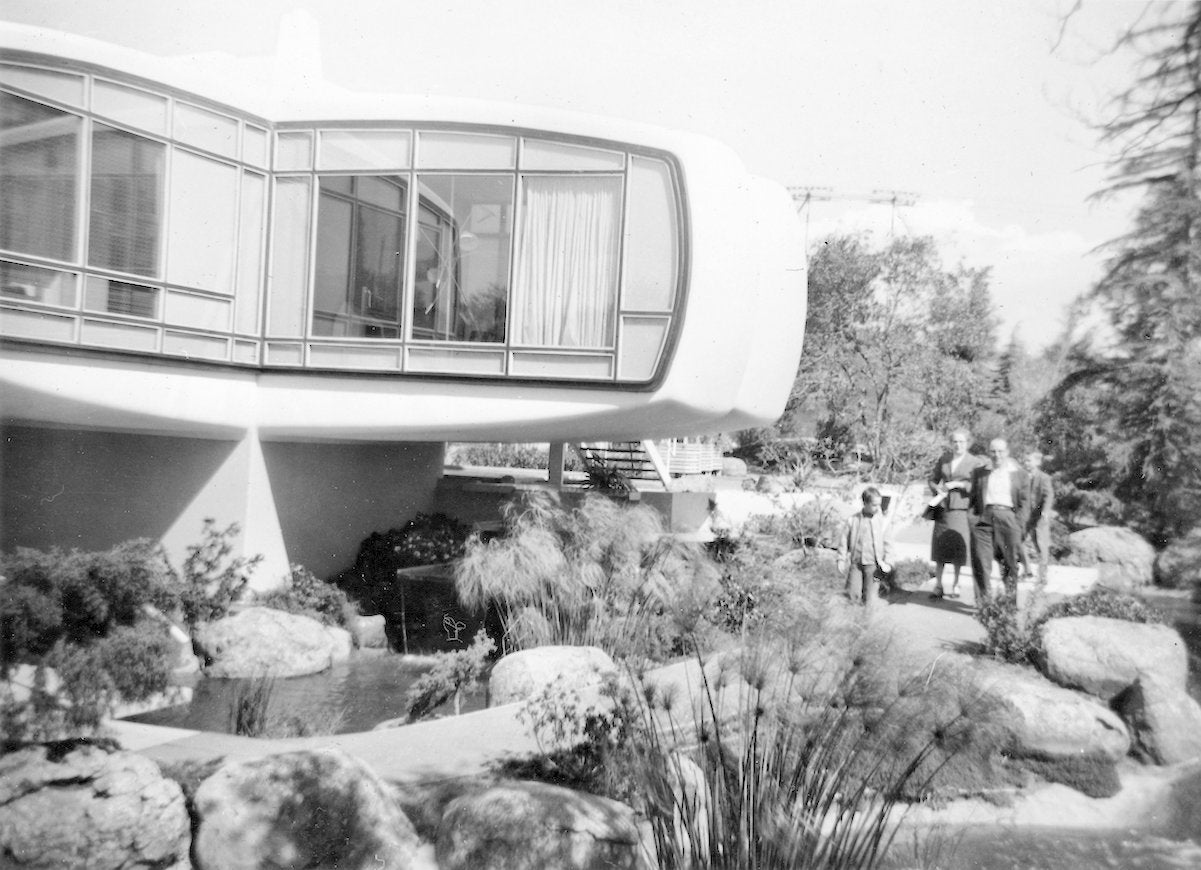

Monsanto House of the Future in Disneyland

Wikimedia Commons via Orange County Archives

While no one actually lived in the House of the Future, it offered a glimpse into an imagined future for the all-American nuclear family. Between 1957 and 1967, the Monsanto-sponsored attraction drew visitors to Tomorrowland, enthralled by the large-screen television, microwave ovens, and all-plastic construction (Monsanto was at the time in the plastics business as well as in agriculture and biotechnology.) While the house was eventually demolished—with great difficulty—the concrete foundation remains in place at the park.

Our Favorite Prime Day Deals Are Sure to Sell Out

Prime Day runs July 8 through 11, and Amazon (and many more retailers) have released hundreds of exciting seasonal deals. Check out our favorite products in the sales, from power tools and outdoor equipment to robot vacuums and power stations.