We may earn revenue from the products available on this page and participate in affiliate programs. Learn More ›

Files are easily taken for granted. They’ve been around for thousands of years, predating even the ancient Egyptian culture of the pharaohs and the pyramids. They’re usually relegated to dusty drawers or toolbox trays, the dull tools of drudge work. After all, filing is no fun, and anybody can do it, right?

Actually, if you feel that way about files, thanks to some unimaginative industrial arts teacher, you probably haven’t been properly introduced to these varied and extremely useful tools. If he didn’t light the lamp of knowledge in this particular area of the shop, let’s see if we can’t offer a little illumination.

Files are shaping tools made of hardened steel that smooth wood or metal, removing burrs or rough spots. They can finish off or enlarge holes, and allow wood to be pared and shaved in places where planes and chisels just won’t reach. Some metal files are used to sharpen other tools, including saw and other blades.

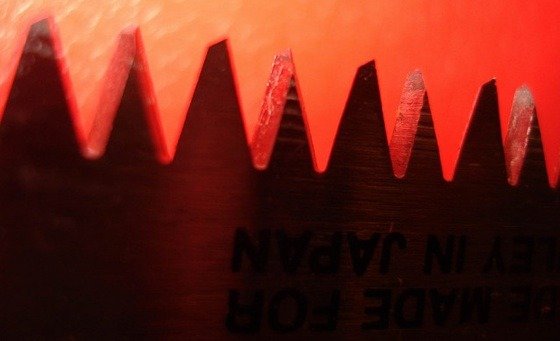

File “Cuts.” Files have raised teeth on their surface that often look like crisscrossing rows of ridges. The teeth do the work of the file, removing small shavings from the workpiece. The “cut” of the teeth on a given file determines the classification to which that tool belongs.

Files with individually shaped triangular projections are called rasps, and are subdivided into wood rasp, cabinet rasp bastard, and cabinet rasp second cut, moving from roughest to smoothest. Files with their points cut in lines are graded coarse or bastard cut (twenty-six teeth per inch); second cut (thirty-six teeth per inch); or smooth (sixty teeth per inch). As a rule of thumb, the longer the file, the coarser are the teeth.

In the case of teeth that are cut in lines, they may be cut in straight lines that angle across the file in one direction or in two. Double-cut files are best suited to rough filing, single-cut for fine or finish filing and sharpening.

Shapes and Sizes. Files are sold in a multitude of shapes and sizes – more than six hundred, in fact. But if you want to invest in only one file, the half round wood file is probably the handiest file in a woodshop. It’s flat on one side and rounded on the other, so it can round concave surfaces (with the half-round side) or smooth flat or convex areas (with the flat one). It’s double-cut, and comes in a great variety of lengths, but a ten-inch half round is a versatile size. The cabinet file resembles the half-round wood file, though it’s thinner and has finer teeth.

Next on the purchase list would be a mill file. The surface of a mill file is always single-cut. Mill files handle fine finishing and sharpening jobs; they’ll do drawfiling (of a scraper, for example), smoothing (of wood or metal), and trueing of edges. They are tapered in width and thickness and belong in every workshop.

The general-purpose flat file is perhaps the most common file, flat on both sides, resembling the mill file. The flat file is sold in main lengths (the smallest will fit in your palm, the longest is hall a yard long) and in different cuts. It’s used primarily by machinists for the fast removal of metal, squaring holes, and making grooves. A hand file is a flat file with one “safe” edge (i.e., with no teeth).

There are round files, square files, and files that are triangular in section. The round rat-tail file is most useful in neatening up small openings, corners, or notches; these files are usually double-cut and tapered. The chain-saw file is also round, but not tapered.

Square files make neat, square corners in openings; they’re essentially flat files. Triangular tapered files are indispensable for handsaw sharpening .

Rasps, too, are sold in varying profiles. The cabinet rasp and half-round wood rasp both have a flat side and a rounded side and are useful for the rapid removal of wooden stock. The equivalent of the metalworker’s mill file is called a wood file: It, too, is single-cut, and is used for finishing wood surfaces. The flat wood rasp is a flat file, though it has the individually cut teeth characteristic of a rasp. Round wood rasps are sold in a variety of grades.

File Care. Treat your files respectfully. They may look indestructible, but they actually are quite brittle, and will snap in two if too much pressure is applied. Don’t try to clean a file by striking it against your vise or any other hard object.

The areas between the file teeth tend to become clogged with debris that can render a tool close to useless. Clean your files regularly, using a file brush or file card. The file brush has two brushes, one on either side, one coarse and one fine. The file card is a clever design featuring wire picks on one side that will loosen the filings and a brush on the other for whisking them away. Whatever your cleaning tool, brush it in a direction parallel to the line of the file’s teeth. One old-timer’s trick I favor after cleaning a metal file is to rub chalk into the voids between the teeth. This will help to prevent filings from accumulating there.

Surfoams. An alternative to the traditional rasps and files is the surfoam. The most common variety has a hollow aluminum body that looks a bit like a simplified block plane. Other types are longer (resembling a jack plane) or even long and cylindrical (like a large rat-tail file). Mounted to each are replaceable steel blades.

The teeth are formed by a stamping process that produces raised teeth and leaves the blade perforated (which prevents clogging by allowing shavings to pass through the blade). The raised and rasplike teeth make the surfoam useful in rough work in much the same way a rasp is. Blades are sold in fine, regular, and medium cuts.

Use the same technique as with a file, cutting on the forward stroke, angling the tool slightly to the workpiece. Surfoams can be used to shape or trim plastic, wood, fiberglass, wallboard, and soft metals such as aluminum, copper, and brass.