We may earn revenue from the products available on this page and participate in affiliate programs. Learn More ›

Shopping for a new home can be challenging, especially when there are seemingly endless options online. While newer homes often fall into a category called neo-eclectic, older homes have distinguishing characteristics that help identify their style or type. Knowing the traits of house styles makes it easier to narrow down the field because search terms can be more specific. However, many of us do not know the correct names of house styles and types.

The following are some of the more popular house styles found in the United States, organized chronologically by when they first appeared. Learning about these 20 house types and styles will make it easier for everyone to find their dream home.

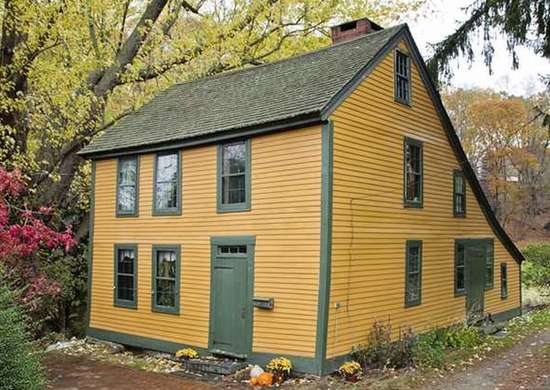

1. Saltbox

When a one-story lean-to addition, or linhay, is added to the rear of an I-House, the result is a distinctive structure known as a saltbox. The name for this style of house derives from the similarity of its shape to 18th-century wooden salt containers. These homes typically have two stories in front and one story in the back. Some have more than one addition.

The sharply sloping roof was sometimes oriented to the north to act as a windbreak. In the South, this form is referred to as a catslide roof.

Pros: The simple geometry of a saltbox home often offers more space, natural light, and interior flexibility than a traditional I-House or Cape Cod.

Cons: Because a saltbox house is usually the result of one or more additions, there can be some discontinuity with the interior and exterior finishes. Adding a second floor to the one-story lean-to can be expensive.

2. Cape Cod

Among the earliest and most common folk building types in New England, the Cape Cod house began appearing in the early 18th century. While the original version was typically an asymmetrical one-half Cape (three bays wide with the door placed at far left or far right) or three-quarter Cape (four bays wide with the door in the second or third bay), the later symmetrical full Cape, with its one-story eaves and front 5-bay central entry plan is more typical today. These side-gabled houses are two rooms deep, sometimes with a series of smaller rooms along the back.

Original Capes had enormous central chimneys. The roof line begins just above windows and it is usually steeply pitched. Early Capes were built before the railroads and required significant labor and hand tooling of materials, so these homes were characteristically modest in interior space and simple in detail. Their low ceilings and few rooms, however, made them easier to heat. For those who desire more livable space in an original Cape Cod house, dormers are a frequent renovation option.

Pros: Cape Cod homes are efficient to heat, and the simple design and floor plan make them easier to update than other house styles.

Cons: They are difficult to cool, tend to be much smaller than other common domestic home styles, and offer very limited architectural detail.

3. Shotgun

Found primarily in the South, shotgun houses are one-story, one-room-wide structures that make the most of narrow lots in urban settings. The name comes from the construction style, which maintained a front-to-back alignment, theoretically allowing a shotgun blast to go from the front door out the back. This layout also means that you need to walk through each room—living room and bedrooms—to get to the kitchen in the back.

When several are grouped together, there are no side windows; in the South, front porches are common. Two to three rooms deep, these houses possess a form that is believed to have descended from West African and Caribbean dwellings. While early versions are very simple with flat roofs, later shotgun homes are highly ornamented with detailed porches and facades with gabled fronts.

Pros: Highly detailed shotgun homes are charming and modest, with a simple layout that is easy to heat and cool, making this house style ideal for those who value tiny homes and minimalist living.

Cons: Shotgun homes are small and lack interior hallways, which means that privacy isn’t a priority. Homeowners will have to walk through bedrooms to get to the rooms in the back or front of the house.

4. I-House

Two stories high but only one room deep, these modest houses earned their name when it was determined that many of the original builders hailed from Illinois, Iowa, and Indiana. The I-House developed domestically from a British folk style and predated the railroad, so materials and access to craftsmen was more limited. These houses are usually quite simple in material and form, and made humble demands on small lots and pocketbooks.

Usually built eaves-front, these gable-roofed homes became even more popular after the railroad. These later I Houses had more detailing, with porches and extensions.

Pros: The compact design of the I-House makes it easier to heat than other styles, and its simple form makes additions easier.

Cons: I-Houses that haven’t been extended or upgraded are so simple that they may not provide the desired curb appeal and charm that many shoppers want from an old home.

5. Side Hall

While they appear to be similar to gable-front shotgun houses, side hall homes also can be two stories and still offer the convenient feature of a hallway on one side. This side hallway is where this house type gets its name, and it allows residents to move through the home without having to walk through bedrooms or common spaces.

Most are slender, simple homes and were constructed of masonry or wood. The facade may be articulated with wide, divided bands of trim in the gable end. Often the Side Hall house type includes detailing with corner pilasters and columns. Some have porches or sidelights.

Pros: Side halls maximize lot space while offering compact living, which can be perfect for those who enjoy simple and efficient floor plans.

Cons: For small lots, side hall houses offer the condensed floor plan of a shotgun home but with the privacy and convenience of a hallway. They are usually situated close to the street, however, to maximize space.

6. Gable-Ell

Widely popular across the United States after the arrival of the railroad, these one- or two-story wood-frame homes feature a central, gable-front mass with an intersecting, perpendicular wing of the same height, effectively creating an L-shaped structure. This style is also known as a gable-front-and-wing home. If a wing appears on both sides of the gable block, it becomes a tri-gable ell.

Some gable-ell homes were originally I Houses, while others were built as a unit with a uniform roofline. Porches are common where the two blocks intersect. These homes often have clapboard siding and double-hung sash windows. They may display a wide array of stylistic ornaments, and many are spacious.

Pros: The gable-ell house offers more flexible interior spaces and less formal exterior massing. Many include outdoor living with detailed porches.

Cons: With a more complicated roofline, repairing and replacing the roof and maintaining the exterior can be more involved.

7. Dutch Colonial

Often with side-gabled or side-gambrel roofs with little overhangs, the typical one-story Dutch Colonial house style began appearing in the mid-1600s throughout what is now New York, New Jersey, and neighboring states. These houses were typically made from brick or wood and included features like divided Dutch doors, designed to keep livestock out of the house.

While the early versions were brick or stone with steeply pitched gabled roofs, in the mid-1700s the gambrel-style roof became more prevalent on these homes.

Pros: The Dutch Colonial offers one-story living with charming and practical touches like Dutch doors and gambrel roofs that offer expansive space in the attic.

Cons: For those who desire a large home with multiple stories, the classic one-story Dutch Colonial isn’t the right pick.

8. Spanish Colonial

This one-story house style began appearing in the Southwest and Florida during the 1600s. In contrast with the Dutch Colonial, Spanish Colonial homes have thick masonry walls and shallower roofs, ranging from low-pitched to flat; some have flat roofs with parapets.

Original homes in this style had multiple entry doors and small window openings with shutters that could be closed from the interior. Narrow porches, internal courtyards, and half-round roof tiles are common on these homes. A modern version of this style, called Spanish Colonial Revival, includes arched windows, stucco exteriors, and second floors with cantilevered balconies.

Pros: Because Spanish Colonial was designed for warm climates, it is easier to keep cool than other larger homes.

Cons: The layout of the original Spanish Colonial, with multiple entry doors and small windows, doesn’t fit with most modern living.

9. Georgian

Often what many think of when they hear the word “colonial,” the Georgian home dominated the English colonies through most of the 1700s. This style presents as stately and formal, and variations exist that range from single-family homes to townhouses.

A Georgian home usually has a symmetrical facade, paneled door, cornice with dentils or other decorative molding, double-hung sash windows, and a row of small windows above the door. Roof dormers are common. The entry is frequently decorated in a classical style with pediments, pilasters, fanlights, or columns.

Pros: The Georgian style offers rich curb appeal with symmetrical massing that makes it easy to furnish rooms.

Cons: Many Georgian homes don’t offer front porches, and it can be difficult and expensive to match the ornate trim typical of these houses.

10. Adam

Some architectural historians call this style Adam, while others refer to it as Federal. Both terms describe the same style, which followed close on the heels of the popular Georgian. The Adam style resembles Georgian in many ways, yet there are distinctions.

The Adam house usually has a symmetrical facade with dentil molding at the cornice. It is typically two rooms deep with double-hung sashes, and the roof is usually side-gabled. The easiest way to tell the difference is the shape of the window above the entry door. If it is elliptical or semicircular, it’s an Adam house. As well, Adam-style homes are more likely to have an original front porch.

Pros: A highly detailed and sophisticated house style, the Adam offers a symmetrical appearance and plan that easily accommodates modern living.

Cons: The Adam house’s iconic elliptical fanlight can be expensive to replace or repair.

11. Greek Revival

For a few decades starting in the 1830s, the Greek Revival house style dominated domestic architecture. Because of its popularity, some dubbed it the “national style.” With classical columns supporting a porch or portico and wide-trimmed pedimented gable, Greek Revival houses are easy to spot. These homes are usually found in the eastern half of the United States.

The windows were commonly six-pane sashes, and there were often small frieze-band windows set into the wide trim below the cornice. However, doors usually received more ornamentation than windows.

Pros: These grand homes offer rich curb appeal for those who appreciate traditional styling.

Cons: Not often found in Western states, the Greek Revival features heavy detailing that can be time-consuming to maintain and not budget-friendly to fix.

12. Queen Anne

The most commonly seen type of Victorian home in the United States, the Queen Anne is often simply referred to as “Victorian” by real estate agents even though that broad category includes Second Empire, Shingle Style, Richardsonian Romanesque, and Folk Victorian homes too.

Like most Victorian homes, the Queen Anne is not symmetrical in massing. The style includes spindlework and an off-center porch. What distinguishes the Queen Anne from other Victorian homes are its steeply pitched, irregularly shaped roof; textured shingles used on portions of walls; a dominant front-facing gable; and “gingerbread” ornamentation.

Pros: A charming house style that’s fun to look at and extremely photogenic, the Queen Anne offers ample space with unique room shapes and sizes.

Cons: For those who like minimalist designs, the Queen Anne is not a winner. The highly detailed ornamentation and asymmetrical facade and floor plan make it more challenging to furnish, heat, and cool.

13. Colonial Revival

Historically, Colonial Revival refers to a rather broad time period architecturally that encompasses Dutch, French, Spanish, Georgian, Adam, and Classical styles. A Colonial Revival house is typically a one- or two-story rectangular, eaves-front symmetrical building with a central entrance and a paneled door. An entry porch with classic columns and pediment usually dominates the facade.

A Colonial is typically two rooms deep with a staircase in the center or at one side. Cladding is commonly clapboard or brick, and windows are usually multipaned double-hung sashes. Original dormers and wall projections are very rare. Deviations may also include a half-plan, with the main entry at the far right or left of a three-bay facade.

Pros: The Colonial Revival home offers a grand entrance with statement-making curb appeal, and it usually provides a great deal of interior space.

Cons: Some who prefer a more casual lifestyle may consider the Colonial Revival too conservative, rigidly planned, and formal.

14. Tudor

One of the easier house styles to spot, the Tudor distinguishes itself from the rest of the neighborhood with decorative half-timbering, tall windows, patterned stonework, and a steeply pitched roof reminiscent of Medieval English homes. The facade usually offers a dominant cross gable with a mini-gable-articulated door.

Typically clad in stucco, the Tudor-style home often has wood wall cladding, double-hung windows, entry porches, and varied eave heights. Some offer semi-hexagonal window bays, battlements, and cast stone trimwork.

Pros: For those who fancy living in a storybook-style home, the Tudor offers ample detailing and cozy spaces that conjure up images of fairy tales.

Cons: Maintaining stucco can be more difficult than caring for other types of exterior wall cladding because of the lack of skilled tradespeople who still practice the craft. The other detailing typical of this home style may require hiring professionals with special skills, increasing maintenance and renovation costs.

15. Classic Cottage

Similar to the Cape Cod but more like a one-story American Foursquare (see below), the Classic Cottage has a slightly higher eaves-front wall that can accommodate small windows in the upstairs knee wall. Roofs are proportionately shallower and, like the American Foursquare, usually have a central dormer. Chimneys may appear in the middle or at either end. Windows are usually multipaned double-hung sash, and the main entry is typically centrally located within a front porch.

This evolution of the basic Cape came when builders learned that a minor modification brought more usable space and light to the upper floor, increasing square footage and utility. Although it’s a residential style, this form was also used in some early schoolhouses.

Pros: The Classic Cottage offers the extension of outdoor living with a front porch, and it often provides more livable space than a Cape Cod.

Cons: Just like the Cape Cod, this house style can be tough to keep cool during hot weather and requires more exterior maintenance, as it has more outdoor surfaces and edges where two different types of materials meet.

16. Craftsman

A Craftsman home has a low-pitched roof with a very wide overhanging eave. Typically, the Craftsman is a one-story house, but these low-yet-broad dwellings often have large porches with columns and sloping sides, exposed rafters, and a roof dormer set in a gable, hip, or jerkinhead (clipped gable) roof. The exposed rafters are sometimes just decorative and often embellished. In the more detailed Craftsman homes of the early 20th century, the influence of the Arts and Crafts movement is quite noticeable.

Oftentimes, Craftsman homes are mistaken for Prairie homes, which also have wide, low-pitched roofs and are frequently one story as well. Key differences are that Prairie-style homes don’t have exposed roof rafters, do not have tapered columns, and are more likely to have a hipped roof.

Another label often used for Craftsman-style homes is bungalow. While most bungalows are Craftsman homes, not all Craftsman homes are bungalows. During the Craftsman heyday, the Greene brothers, who were noted practitioners of the style, designed a series of Craftsman homes that were referred to as “ultimate bungalows” and were featured in popular magazines. This led to pattern books being created based on their designs. The term “bungalow” is often used to describe vernacular versions of Craftsman homes.

Pros: Original Craftsman homes usually have ample porches that create an inviting outdoor room, and the interiors are often filled with handcrafted details.

Cons: Many Craftsman homes are modest in interior square footage, especially the typical one-story versions. The overhanging roof can block expansive views in some interior rooms.

17. American Foursquare

Economical to build, these two-story square homes with hipped or gable roofs saw great popularity in the United States in the years after 1900. Often this house type is found in the Prairie style, which includes a low-pitched roof, wide overhanging eaves, and frequently a dormered attic and a wide front porch. A reaction to the irregular shapes and extensive ornamentation of the Victorian era, these boxy four-room-over-four-room homes are among the few truly American styles.

While some incorporated charming moldings and other highly crafted details like built-ins and window seats, the generally clean styling and simple design of the typical Foursquare met with quick favor, and they soon began popping up in small towns across the country, becoming an American classic. Some architecture experts debate whether the American Foursquare, like the shotgun and gable-ell, is a distinct house style or merely a house type.

Pros: The American Foursquare blends the craftsmanship of the early part of the 20th century with the availability of mass-produced commodities, resulting in a home that, while usually quite simple, still displays a number of unique crafted features.

Cons: Because the plan is based on a four-room layout, interior hallways and original storage spaces are usually limited. Renovated American Foursquares may include a powder room on the main floor, but original, unremodeled Foursquares most likely lack this feature and don’t have sensible place to add one within the original footprint.

18. Ranch

Ranch homes fall into the category of modern home styles. The one-story homes often have a simple low-pitched gable or hipped roof. Their low-to-the-ground, horizontal appearance was a reference to homes of the Southwest, but their prevalence stemmed from the crushing demand for affordable housing at the close of World War II.

As young families settled into newly developed suburbs, they gravitated toward homes that offered modern conveniences like Ranch homes with integral garages. Many include the iconic front picture window, along with either traditional double-hung sash windows or modern casement, slide, or awning windows. The ranch dominated home building during the 1960s and is still a popular new home type today, with the added attraction of facilitating easier aging-in-place.

Even though the classic Ranch home is one story, there is a later 1970s version that’s called the Raised Ranch. This is a two-story house. A main floor is on top of a raised foundation, which creates an additional lower level and an opportunity to include full-size windows.

Pros: The style is ideal for larger properties where a home’s floor plan can spread out, and it is often the preferred home for older Americans who want to be able to age in place.

Cons: For those who prefer to live in a dense community, a ranch-style home would be a tough find. They usually require and come with more acreage, which means more yard work for the homeowners.

19. Split-Level

During the 1950s, split levels became popular. The split design separated activities by levels with half-story wings. In a split-level, bedrooms are separate (and usually on a higher level) from the kitchen and family areas. Every function has a level and is distinct from the other levels. The sunken garage is one of the new home features characteristic of the split-level house.

Many of these homes assumed characteristics of the Craftsman movement, with a low roof, widely overhanging eaves, and ribbons of windows at different living levels. They are less common in the West and South.

Pros: Split-level homes offer separation of living functions, which can be very appealing to multifunctional modern lifestyles.

Cons: The split-level holds little appeal for those who enjoy an open floor plan. Also, these homes benefit from zoned heating and cooling.

20. Neo-eclectic

After the few decades that Modern architecture dominated the landscape of residential design, a neo-eclectic aesthetic took over. While these homes nod toward specific housing styles of the past, the neo-eclectic home isn’t authentically one particular style.

Just as most of the popular domestic architectural styles of the past 200 years have a modern version—for instance, there are neo-French, neo-Tudor, and neo-Victorian homes—there is a neo-eclectic style. For example, a home that is predominantly neo-Colonial may have the window styles, roof type, and facade configuration of a Colonial Revival, but it may also have an attached garage, vinyl siding, and a split-level interior. Today, most suburban homes fall into the neo-eclectic category.

Pros: The neo-eclectic home offers some of the popular detailing elements and overall look of a particular historic architecture style but is designed and built to suit modern lifestyles, with features such as attached garages, larger kitchens, and multiple bathrooms. These houses are also usually easier to maintain because they are built with modern, low-maintenance materials.

Cons: For those who value living in a historic home that embodies a true style, the neo-eclectic aesthetic is lacking. These houses may have details that mimic the craftsmanship of an earlier era, but they may also be made from materials that aren’t authentic to the original style, such as vinyl, fiberglass, or other man-made materials.